by Gary Mintchell | Feb 8, 2018 | Leadership, Productivity

I guess I’m on an entrepreneurial kick this week. Maybe I’m getting psyched for next week’s ARC Forum in Orlando where I will be interviewing many new companies inhabiting the cybersecurity space.

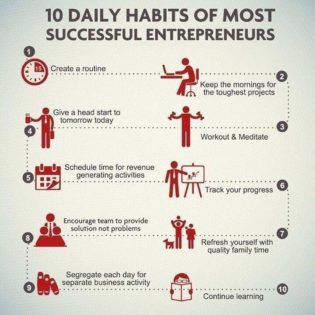

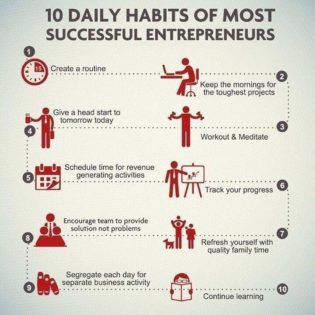

I’m not much on “infographics” and I downloaded this one without noting its source. Note that nowhere on it does this graphic cite its source. However, I read many books, blog posts, and listen to podcasts on the subject of daily habits. This one reflects most of what I’ve learned.

However number one–create a routine–actually needs an entire infographic devoted just to it. Maybe that will be my next attempt at looking at the personal and people side of this business.

I’ve been involved in several start ups. These all make sense. Although these look pretty drawn out. Usually life happens that screws the thing up. But returning to the pattern is key.

by Gary Mintchell | Feb 6, 2018 | Leadership

Many entrepreneurs or people with entrepreneurial thinking within companies read this blog. Many more of you should be–entrepreneurs, that is.

I picked up this bit of wisdom of Elon Musk from the Abundance Newsletter of Peter Diamandis (Singularity University). Check out “Deconstructing Elon Musk.” Diamandis distilled three key parts of Musk’s genius. I recommend going to the Website and checking out the article in its entirety as well as subscribing to the newsletter. I hope this stirs some passion.

The three parts are

- Deep-rooted passion

- A crystal-clear massively transformative purpose

- First-principles thinking

A brief description of each to whet your appetite.

Deep-rooted passion: “I didn’t go into the rocket business, the car business, or the solar business thinking, ‘This is a great opportunity.’ I just thought, in order to make a difference, something needed to be done. I wanted to create something substantially better than what came before.” – Elon Musk

After selling PayPal, with $165M in his pocket, Musk set out to pursue three Moonshots, and subsequently built three multibillion-dollar companies: SolarCity, Tesla and SpaceX. Ultimately, it was his passion, refusal to give up, and grit/drive that allowed him to ultimately succeed and begin to impact the world at a significant scale.

A Crystal-clear massively transformative purpose: Musk’s MTP for Tesla and SolarCity is to accelerate the world’s transition to sustainable energy. To this end, every product Tesla brings to market is focused on this vision and backed by a Master Plan Musk wrote over 10 years ago. Elon’s MTP for SpaceX is to backup the biosphere by making humanity a multiplanet species.

“I think fundamentally the future is vastly more exciting and interesting if we’re a spacefaring civilization and a multiplanet species than if we’re or not. You want to be inspired by things. You want to wake up in the morning and think the future is going to be great. And that’s what being a spacefaring civilization is all about.” – Elon Musk

First-principles thinking: (from an interview with Kevin Rose–who has a podcast you should subscribe to) “First principles is kind of a physics way of looking at the world. You boil things down to the most fundamental truths and say, “What are we sure is true?” … and then reason up from there. Somebody could say, “Battery packs are really expensive and that’s just the way they will always be… Historically, it has cost $600 per kilowatt hour. It’s not going to be much better than that in the future.” With first principles, you say, “What are the material constituents of the batteries? What is the stock market value of the material constituents?”

It’s got cobalt, nickel, aluminum, carbon, some polymers for separation and a sealed can. Break that down on a material basis and say, “If we bought that on the London Metal Exchange what would each of those things cost?” It’s like $80 per kilowatt hour. So clearly you just need to think of clever ways to take those materials and combine them into the shape of a battery cell and you can have batteries that are much, much cheaper than anyone realizes.”

by Gary Mintchell | Feb 2, 2018 | Education, Leadership

How about you? Do you feel like you know everything you need to know? Do you hate asking people for directions?

Whether you are in business or ministry or family–do you have all the answers?

While I usually write about technology, I’ve learned the hard way that people are as important as the technology. I’ve seen my technology implementations fail because of the failure to get people on board. And how often have we seen people in critical situations fail to communicate at the cost of people’s lives? All through failure of asking appropriate questions.

Edgar H. Schein writes in his book, “Humble Inquiry: The Gentle Art of Asking Instead of Telling,” that many people would rather fail than admit their dependency on another person. That is, by asking them a question and admitting that someone else has an answer.

How about succeeding together?

Try Humble Inquiry. Asking questions implies that someone knows something I don’t–even if they are a subordinate, or younger than I, or from a different background. I must humble myself to ask someone placing myself in a position of learner to someone superior to me in this situation. It is the opposite of what we are taught in our culture which places emphasis on telling.

I’ve talked often about the skills of listening. Often we need to ask questions to elicit something to listen to.

Schein says, “The kind of inquiry I am talking about derives from an attitude of interest and curiosity. It implies a desire to build a relationship.”

We must slow down to ask and then listen.

Again Schein says, “I find that the biggest mistakes I make and the biggest risks I run all result from a mindless hurrying. If I hurry, I do not pay enough attention to what is going on, and that makes mistakes more likely. More importantly, if I hurry, I do not observe new possibilities.”

Let’s think about this comment in the context of hazardous situations

He points out in our “Do and Tell” culture, the most important thing we need to learn is to reflect. Before doing something, apply Humble Inquiry to yourself. “Ask ourselves: What is going on here? What would be the appropriate thing to do (Wow, there are hundreds of men right now who wish they had asked themselves that question)? On whom am I dependent? Who is dependent upon me?”

In other words, become more mindful.

“The toughest relearning, or new learning, is for leaders to discover their dependence on their subordinates, to embrace Here-and-now Humility, and to build relationships of high trust and valid communication with their subordinates.”

Schein was an MIT professor and business consultant. You can substitute parent for leader and use the ideas in family.

Read and digest the book. It’s short and not technical. Good read.

by Gary Mintchell | Jan 25, 2018 | Leadership, Productivity

Sometimes we must step back from a narrow view of technology and consider how (or if) we make moral decisions.

I saw this in a blog called Big Think. It’s a good starting place for thinking.

A few weeks ago we talked to Dr. Fred Guy, Director of the Hoffberger Center for Professional Ethics and associate professor at the University of Baltimore, who told us about his goal to create a Philosophy Camp for adults and why such an initiative is important.

Adults tend to become lazy with their thinking, backing into moral and ethical wrongdoing without noticing fully what they’re doing. As he says:

“Adults are so busy and focused on so much other than ethical issues that we don’t often stop to think coherently about what our moral principles really are. Or what we think of our own moral character. We just assume we’re good people and let it go at that.”

Guy urges us to revisit and refine our moral code with the help of some good philosophical thinking.

He offers a series of questions that we can use to examine the case we are faced with. He calls it the ABCD Guide to Ethical Decision-Making and it goes like this:

A: Awareness: Are we aware of the ethical issue we’re a part of?

• Do we know all the facts?

• Is this an ethical problem or a legal one? Or both?

• Can it be resolved simply by calling upon the law or referring to an organizational policy?

• Am I aware of the people involved in this case and who may be affected by my decision and action?

B. Beliefs: What are my moral beliefs? What do I stand for? Most of us know if we give it some serious thought. What we decide and do in a given ethical situation depends on our moral beliefs, principles, values and virtues — or lack thereof. We may ask:

• What kind of person am I? Would I want this done to me or to those I love?

• Would it be responsible of me if I thought everyone should act this way in my situation?

• Am I setting a good example or a bad example?

• Can I continue to respect myself given the probable outcomes of my action?

C. Consequences: Use moral imagination to think about consequences for ourselves and others, not only now but into the future as well. It’s the ripple effect. Our actions may indirectly affect others we don’t know.

• Who may be affected by my decision?

• How may my decisions/actions affect other and myself?

D. Decision: Given the facts of the case, our own personal ethics, and the consequences that our decision and action will have on others, what is the best thing to do in this case?

• Would I mind my action being broadcast on the six o’clock news?

• Could I justify my actions to my family and close friends?

• What advice would I give to a close friend who had the same decision to make as I do?

Just taking the time to pause and go over these questions when we are making an important decision, can take us out of the default moral mode we live in and, hopefully, out of the trap of just assuming we’re good people, without truly delivering on that assumption.

by Gary Mintchell | Jan 15, 2018 | Leadership, Workforce

Looking for the source of innovation in manufacturing technology. Not only am I planning for direction in 2018, I’m in conversations about where lies the excitement.

OK, so it’s been two months I’ve been digesting some thoughts. In my meager defense, November and December were very busy and hectic months for me. Still lots going on in January as I gear up for the year.

Last November, I quoted Seth Godin:

Like Mary Shelley

When she wrote Frankenstein, it changed everything. A different style of writing. A different kind of writer. And the use of technology in ways that no one expected and that left a mark.

Henry Ford did that. One car and one process after another, for decades. Companies wanted to be the Ford of _____. Progress makes more progress easier. Momentum builds. But Ford couldn’t make the streak last. The momentum gets easier, but the risks feel bigger too.

Google was like that. Changing the way we used mail and documents and the internet itself. Companies wanted to be the Google of _____. And Apple was like that, twice with personal computers, then with the phone. And, as often happens with public companies, they both got greedy.

Tesla is still like that. They’re the new Ford. Using technology in a conceptual, relentless, and profound fashion to remake industries and expectations, again and again. Take a breakthrough, add a posture, apply it again and again. PS Audio is like that in stereos, and perhaps you could be like that… The Mary Shelley of ____.

So I asked on Twitter “Who will be the Mary Shelley of automation?

I’m sitting in a soccer referee certification clinic when I glance at the phone. Twitter notifications are piling up.

Andy Robinson (@Archestranaut) got fired up and started this tweet storm:

Gary… why do you have to get me fired up on a chilly November morning! I’m not sure we have any.. at least at any scale. And the more I’ve pondered this more the more I consider the role or culpability of the customer. Buyers of automation at any scale tend to be 1/

incredibly conservative. If they are ok with technology that isn’t much more than a minor evolution of the existing then we aren’t going to get anywhere. Recently I devoured Clayton Christensen’s The Innovator’s Dilemma. I keep trying to figure out how a small player 2/

with disruptive tech can move our industry. There are pockets and potential but ultimately if there isn’t enough uptake by customers willing to take a risk then we don’t move forward. Considering all this I “think” I have figured out one potential causal factor. 3/

If you look at where the fastest innovation is happening it’s in software. Is the majority of the innovation coming from vendors or asset owners. it’s asset owners. Amazon, Netflix, AirBnB, etc. are all doing amazing things and taking risks writing new code for their systems4/

Having been an asset owner and vendor I can tell you for a fact I was way more willing to take risks when I was the owner. As a vendor I want to deliver a solution to spec with minimal risk. Fundamentally product companies are doing the same thing. Just good enough with 5/

minimum risk to supply chain, warranty repairs, reliable field operations etc. Even platforms like Kubernetes that appear unaffiliated were developed by asset owners like Google, taking risks and pushing the boundaries. The Exxon work with open automation “has” this 6/

potential but I don’t know if the willpower up and down the chain and left and right with partners is going to be there. It takes incredible willpower to take risks and accept that there will be blow back and consequences in the form of loss of political capital and failure. 7/

So maybe it all boils down to the fact that until we as an industry find a place where failure is acceptable and even celebrated on a small scale we will continue to innovate at a speed somewhere between typewriters and vacuum cleaners. 8/

is it any wonder we have such a hard time attracting young talent? Pay is good and challenges to solve real problems are there. But looking 20 years out we are still doing same things, just a new operating system, faster Ethernet, and new style of button bar on the HMI /endrant

He asks some good questions and provides some interesting insights.

I’ve had positions with companies at different points of the supply chain. He makes sense with the observation that the asset owners may be the most innovative. My time in product development with consumer goods manufacturers taught me such lessons as:

- Fear of keeping ahead of the competition

- Relentless concentration on the customer

- Not just cost, but best value of components going into the product

- Explaining what we were doing in simple, yet provocative terms

Today? I’m seeing some product companies acquiring talent with new ideas. Some are bringing innovative outlooks to companies who find it very hard to take a risk for all the reasons Andy brings up. The gamble is whether the big company can actually bring out the product—and then integrate it with existing products to bring something really innovative to market. They of course have the funds to market the ideas from the small groups.

Next step, do the innovative people from the small company just get integrated into the bureaucracy? Often there is the one great idea. It gets integrated and then that’s the end. The innovators wait out their contract and then go out and innovate again. I’ve seen it play out many times in my career as observer.

Often the other source of big company innovation bubbles up from customers. An engineer is trying to solve a problem. Needs something new from a supplier. Goes to the supplier and asks for an innovation.

I’d look for innovation from asset owners, universities, small groups of innovative engineers and business thinkers. They live in the world of innovating to stay ahead of the competition or just the world of ideas.

I’m reading Walter Isaacson’s biography “Leonardo” right after his one on Einstein. He offers insights on what to personality to look for if you want to develop an innovative culture in your workforce. Wrote about that recently here.

by Gary Mintchell | Nov 7, 2017 | Commentary, Leadership, News

Turning a giant organization that has the great inertia can be likened to turning a large ship at sea. It takes great force and a lot of space. Such is the task of remaking Microsoft.

Satya Nadella has been CEO of Microsoft replacing the combative Steve Ballmer more than three years ago. I’ve seen him speak at conferences at least three times. I’ve talked to many Microsoft people. He truly has turned that big mass toward the future.

Hit Refresh: The Quest to Rediscover Microsoft’s Soul and Imagine a Better Future for Everyone tells Nadella’s personal story, as well as his business and leadership.

He begins personally. The key takeaway is his discovery of empathy. I imagine that that value was in short supply in Redmond during Ballmer’s tenure. Nadella talks about a mentor, but also the birth of a handicapped child and what the family learned while caring for him introducing him to the emotion and value of empathy.

Like most people with an MBA, he was steeped in strategy theories. As he thought about his task as the new leader of Microsoft, naturally he thought about strategy.

His early three-pronged message was

1. Reinvent productivity and business processes

2. Build an intelligent cloud platform

3. Move people needing Windows to wanting Windows

Remembering Peter Drucker’s dictum, “Culture eats strategy,” he also move quickly to change the corporate culture. He includes a few stories revealing how he went about that gigantic task.

His view of what leaders tasks are:

1. Bring clarity

2. Generate energy

3. Find a way to deliver success

He has given much thought to values. These are similar thoughts to what we hear at National Instruments’ gatherings—engineers solving the world’s biggest problems. He urges policy makers, mayors, and others not to try to replicate Silicon Valley but instead to develop plans to make the best technologies available to local entrepreneurs so that they can organically grow more jobs at home—not just in high tech industries but in every economic sector.